Thresholds and Trespasses.

AN EMBODIED EXPLORATION OF BORDERS’ IMAGINARIES.

I checked the point on the map, and I know where I need to go. I reach that point, and yet I need to check again on my phone where that line is: the national border that separates Switzerland and Italy. There is nothing visible on the ground. I move on, and the landscape seems more tidy, more precise, more Swiss. This is a stereotype we often have in Italy, that the Swiss people are more precise. After all, they are famous clockmakers.1 Maybe that is why I expect the landscape to be neater as well, and that is how it looks to me. I may be subject to what Luca Gaeta calls the “pregiudizio del noi” [the us bias].2 We all have some prejudices when we approach the study of a border because it is impossible to strip away our own provenance, which often places us on one side or the other of the line. In my case, I study the Swiss-Italian border as an Italian, and I am aware that some biases are inevitably present in me.

I go back. I cross again and I am once more in Italy. Just a tiny movement, one step, across that line that is only visible on the maps on my phone. I follow the map, moving to another point of the border. There is something more there, a boundary stone that marks it. It is called “cippo confinale” [boundary stone], in legislative terms. The stone bears the date 1921 and the initial letter of the two countries, each on one of its opposite sides of the border. As I stop to have a closer look, it occurs to me that stones have always been used to mark borders. Their use to mark off boundaries and limits is somehow archetypal. They perform the function of markers, tangible signs delimiting specific areas. Francesco Careri, for example, has written on the use of menhirs to sign sacred places or to demarcate boundaries and properties in Sardinia.3 And more, the very Roman god of borders Terminus was personified in a stone, rather than an icon, as explained by Gianluca De Sanctis.4

As I move along the border, I am astonished by the banality of the places that I meet on that significant administrative division. Such a lack of recognizability is not what I had expected. No barbed wires around, no walls. Only at some specific points do I encounter the remnants of old metallic mesh. These are probably traces of the so-called ramina, a wire mesh built by Italy at the end of the nineteenth century mostly as a fiscal barrier to prevent the smuggling of goods, but which has never stopped smuggling completely, just as it has not fully prevented the passage of people.5

The apparent absence of the border contrasts with the map where it is marked as a thick line, well-defined, and clear. It is precisely through cartographic drawings that national boundaries came to exist. Maps were the instrument of political geography discourse to identify borders. Map-making was a form of knowledge that for a long time mostly belonged to the militaries, and many scholars in border studies spoke of maps as hegemonic tools used to control and possess land.6 This is the main reason I decided not to include a map of the places I talk about in this essay.7 Maps show borders as something apparently fixed and impermeable. This is rarely the reality, because borders exist in dynamic ways, traversed by flows passing through their holes, and more – borders are always in motion themselves, as recently elaborated by Thomas Nail in his theory of the border.8 Even the border between two nations like Switzerland and Italy is in motion, despite being a border where apparently nothing happens, an ancient and uncontested border, a “boring” one.9

In a military survey of the entire Italian border completed during the 1920s by the Italian military, the author Colonel Vittorio Adami described the part of the border that touches Switzerland as an “irregular” and “illogical” line, which does not follow the “geographical border.”10 Colonel Adami’s study was commissioned by the Italian General Superintendent of State and is made up of cartographic drawings and textual descriptions of the boundary-line sediment, with a detailed identification of boundary stones.11 According to Colonel Adami, based on certain geographic and cultural characteristics, Canton Ticino should have been part of Italy and the border should have passed further north, but historical events meant that this was not the case. His reasoning was based on the fact that in between the regions of Lombardy in Italy and Ticino in Switzerland, there are many common characteristics. The two regions share the same language, Italian; the same religion, Catholicism; and the same geography, flatland, but still they are divided by the border. Ticino is indeed the last flatland area to the south of Switzerland right before the beginning of the Alps, those mountains that would make a kind of a “natural” border, and yet they do not.

A certain geopolitical discourse of the past has carried forward the idea of the existence of natural boundaries provided by specific geographical elements such as mountains, mostly for reasons instrumental to political interests.12 Even mountains, as much as they can be a topographic division of a territory at a certain scale, have jagged and irregular shapes, and offer different peaks that can act as divisions. To find in them a single line that defines a boundary, a line without thickness and stretching endlessly into the sky as a border is supposed to, is an entirely human construct.

During these visits, I collect photographs of the invisible boundary line one after the other: trees, a bridge, a panoramic point on Lake Lugano, and then more trees. I am aware that the meaning of photographs is always contextual.13 In this case, I feel even more that these photographs only start to make sense when I am telling a viewer that these depict precisely the border itself, in its invisible being. While they do not show directly what they represent, they allude to the abstract nature of cartographies and contradict the reality of maps, exposing the invisibility of the border. The same happens with photographs of aftermaths of events, that is, photographs made in places where something happened, but nothing of that past event is visible. The photos are traces that point to the event itself. They show something that happened but is not visible but still is indexically present in the images.14 By indexicality, I refer to the capability of a sign to point at some object in the context of production in which it comes about. As aptly stated by Hilde van Gelder, the indexical image “is both a trace of and a pointer toward the reality depicted.”15

What clearly is not shown in these photographs are the dynamics of crossing that originate from the border and that keep it alive, while also contesting some of its features. A border, wrote Luca Gaeta, “si conserva insieme alla pratica di cui è confine, altrimenti cessa di essere tale” [is preserved together with the practice of which it is the border, otherwise, it ceases to be].16 It is the horizon of the multiple routine practices of individuals, as well as of multiple collective practices. On this border some historical practices of crossing concern labour. In the second half of the eighteenth century, with the approval of protective labour laws in Switzerland aimed at limiting child labour and establishing regulations on maximum working hours per day, companies from the inner area of Switzerland started to delocalise into Italy to avoid the regulations.17 When the same regulations came into place in Italy, industries started to settle in the Ticino border region and employ Italian workers, who could be hired with a lower wage in comparison to the Swiss inhabitants of the area. An economic differential existed between Italy and Switzerland, so that in Switzerland there was a higher cost of living.

The English language uses the composition of the three words “cross-border workers” to denote such workers. The Italian language uses only one word, frontalieri. This word, which may be translated as “frontier-ers”, displays an embodied dimension of the border in the workers themselves. The workers periodically commuting across the border become some sort of actant of the border itself. The border produces specific spatial practices, which in turn reproduce it. Bodies moving from one side of the line to the other incorporate it and move it.

This historical dynamic is still relevant today. The exchange is favourable for both parties: Factories can take on workers who accept a lower wage, and workers can find working opportunities that would not exist on the Italian side. Yet, there are also contradictions, because the value of labour is perceived to be constantly going down, triggering conflicts between Swiss inhabitants and Italian border-crossers, who are said to be stealing jobs and lowering the cost of labour for everyone, a phenomenon called “wage dumping.”18 At the same time, Italian workers do not feel welcome.

Among the first historical factories were those for tobacco and then textile manufacturing. It reminds me of what came about with globalisation on a larger scale, or in other much more iconic borders such as that between Mexico and the United States, with the maquiladoras, assembly plants of mostly US companies employing Mexican women, companies that exist thanks to special tax exemptions. These kinds of factories are shown in the Swiss artist Ursula Biemann’s video work Performing the Border (1991).

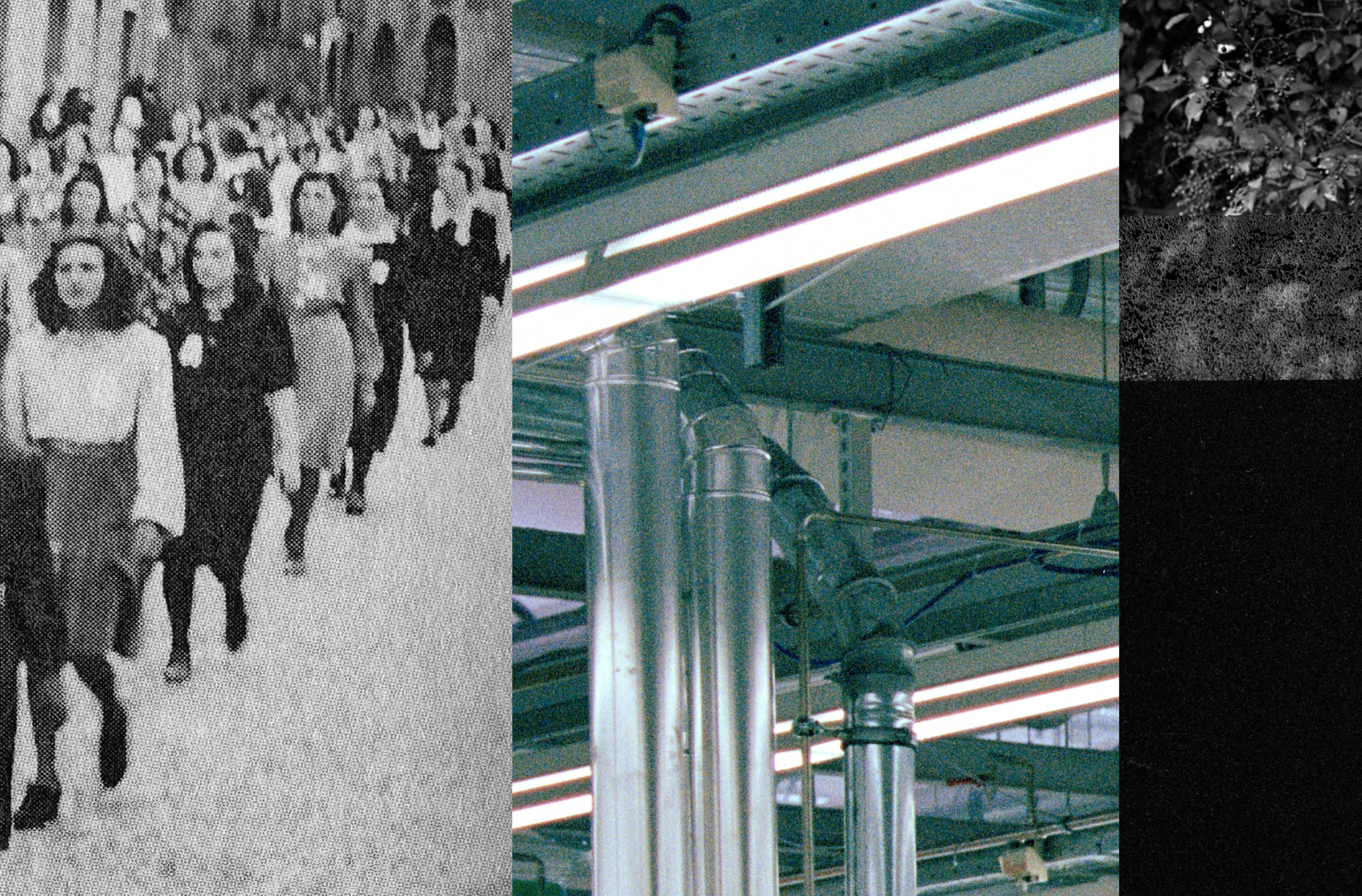

I focus my research on the shirt factory Realini because it is one of the very few old textile manufacturing factories still functioning today in the Swiss-Italian border area, although the owners have changed over time. Those textile companies have mostly moved from manufacturing to logistics, but there are many other companies in other sectors that are active and largely survive cross-border workers. Frontalieri now account for 30 percent of the workers in Ticino.19 The Realini shirt factory opened in the 1920s. Its workers were mainly Italian women. Every day they would reach the border on foot, cross into Switzerland, work there, and get back at the end of the day. While many people commute for job reasons, in crossing that line, those women were subject to a change of citizenship. They did not have the right to vote in the country of their workplace, a technical but substantial detail in considering the status of citizenship from a normative point of view.

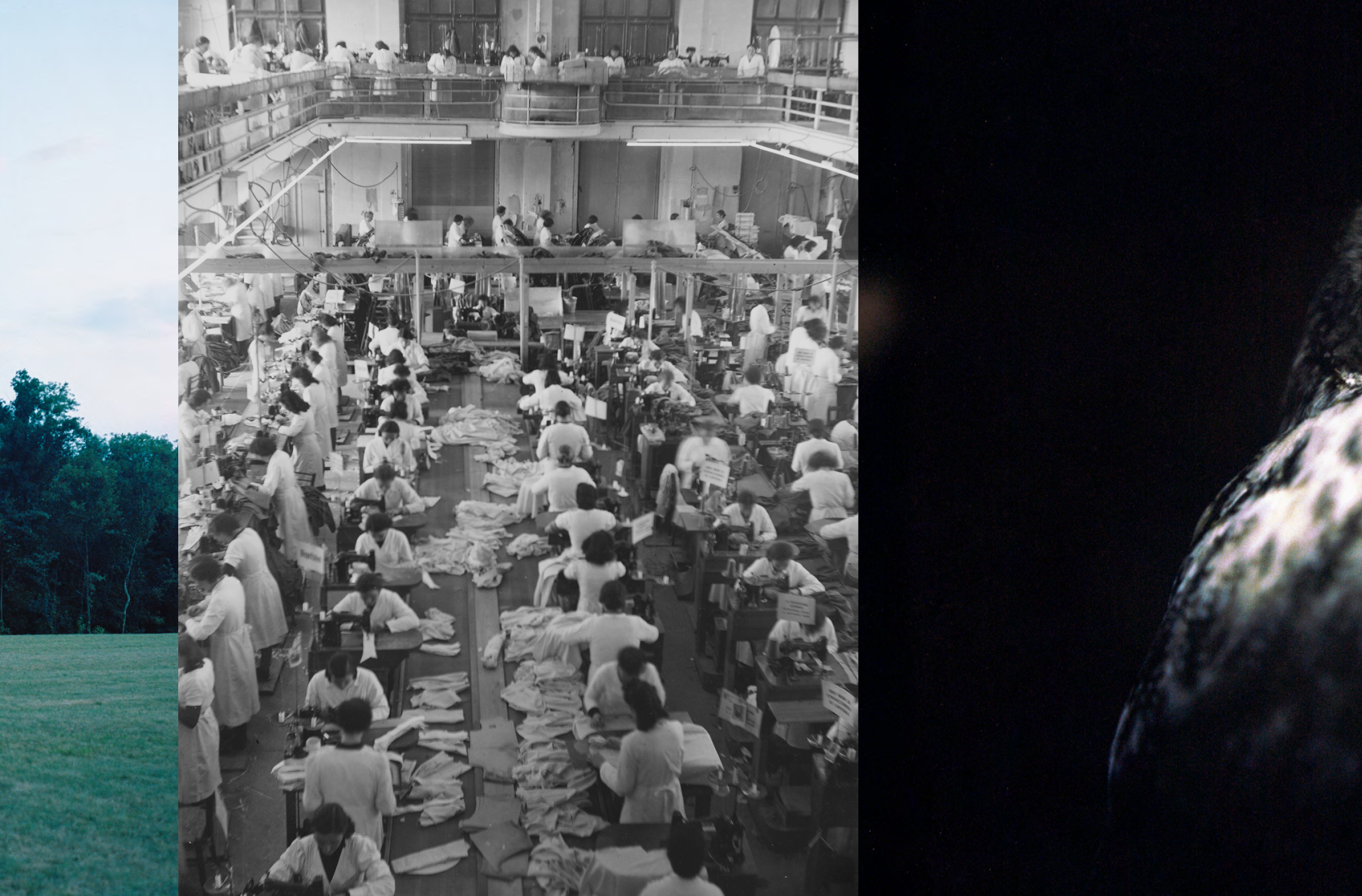

I meet someone who knew the former owner. “Yes,” she says, confirming my question, he decided to open the factory in the Ticino region because of the possibility of employing Italian labour.20 He also hired workers coming from inner Switzerland, who mostly had German surnames. Those workers were destined for the offices, the intellectual part of the factory. I am given some old photographs, probably dating from the 1920s and 1940s. One of these pictures of the factory shows a building with a high inner space, a large central void and a balcony that runs all around the perimeter of the building on the second floor, allowing those up to look down into the workspace, where female workers sewed men’s shirts (Fig. 11).

As I research this factory, I come across this audio interview of some women who used to work there in the 1940s.21 Among other things, they tell an insignificant episode, part of that everyday history that mostly remains unwritten. In the border woods where I paid my first visits to this invisible line, they used to collect lilies of the valley in April and May at the end of their work shift. These white flowers grow from a rhizome; with the light of the sun, they bend and become invisible. So the women went in the night or in the early morning when the white flowers would come out and become clearly visible against the backdrop of dark grass. After the harvest, the flowers would travel to inner Switzerland, where they were sent to be sold for the feast of May First. This way, the women workers of the shirt factory supplemented their salaries.

What surprises me is that nobody mentions the existence of the border there in the woods. The border is completely absent from their narration; its presence seems to be meaningless. Perhaps it only strikes me because I have been studying the geography of that line for months. Yet this absent border created the condition for the existence of the factory where they work and for their daily movements.

I visit one of these contemporary factories in the area. There are still many, even if very few now have to do with the actual production of physical artefacts, since many mostly take care of the logistics of moving goods. It was difficult to obtain permission to take photographs. Mostly, I do not have the authorisation to use these photographs, because of privacy agreements (Fig. 8). I manage to enter the old shirt factory building. I am not sure what I am looking for, but I want to visit it and see its environment. In a corridor, I encounter a statue of a sower-man created in the 1940s. An inscription on the base shows the Latin proverb “qui operator terram suam / satiabitur panibus” and its Italian translation “chi lavora sulla sua terra / sarà saziato di pane,” [those who work on their land / will be satiated with bread].22 I find it peculiar that it is there, where workers mostly used to come from another land.

The new factories’ facilities are efficient and hyper-organised spaces of production. Metallic surfaces, shining lights, and fabrics surround me. Logistics spaces and warehouses are organised with a precise and logical division, where operations are almost completely automated. I walk through some of these spaces. Workers also prepare indications on the production of goods to be made elsewhere, in factories delocalised elsewhere.

The women workers of the past used to walk to the border. Contemporary workers no longer commute on foot; they use cars. At five o’clock in the morning, the border area is filled with cars queuing. Red lights come on when the cars stop; then they turn off when the cars get going. Stillness, movement, stillness: I observe this row of red glows one very early morning, before dawn even breaks, from the balcony of my rented accommodation on the road leading to the border. I am not used to these early hours. I feel dazed. That long strip of lights seems so strange on the road of such a small town. Here the border seems to create a centrality, as if it were a big city.

Many workers leave their cars in parking lots on the Italian side from which depart shuttles that will take them to the factory area. In the production area of the border region, there is no space to park, no space to stop. I also tried to stop when I drove across the border into the industrial area later in the morning, but I found no way to do so. There is no parking for those who do not live there, so I temporarily left my car in a random spot to get a rapid coffee. As I drink it, I cast a few quick checking glances at the neighbouring parking lot, fearing that my short, illegal stay will be fined. I chat with some workers at the cafe. In the border dynamics, their daily life and working life are completely separate, I am told. Switzerland is where the frontalieri work, Italy where they live, with periodic movements from one side to the other, between two different economic and spatial systems linked in an osmotic equilibrium.

In the parking lots that provide a platform for such movements, there seems to be a dislocation of the invisible border. In those places of transit, where cars sit waiting for the workers to come back at the end of their shifts, there have also been other forms of stillness, other transits on hold. These are connected to the so-called migration “crisis” in the area at the border between Como and Chiasso.23 In 2016, there was a massive arrival of migrants, or “people on the move,” to use a more appropriate expression suggested by Amnesty International.24 They were blocked there due to European regulations (the Dublin agreements) stating that a person irregularly entering Europe can only apply for asylum in the first country of entrance in the union.25 In this normative framework, those who tried to enter Switzerland but had already been registered in the European database through their fingerprints in Italy were pushed back to the latter and remained stranded in the border town of Como. Through such operations, the body became an instrument of biopolitical control.26 The peak of arrivals continued until 2019, then decreased dramatically, and then resumed.

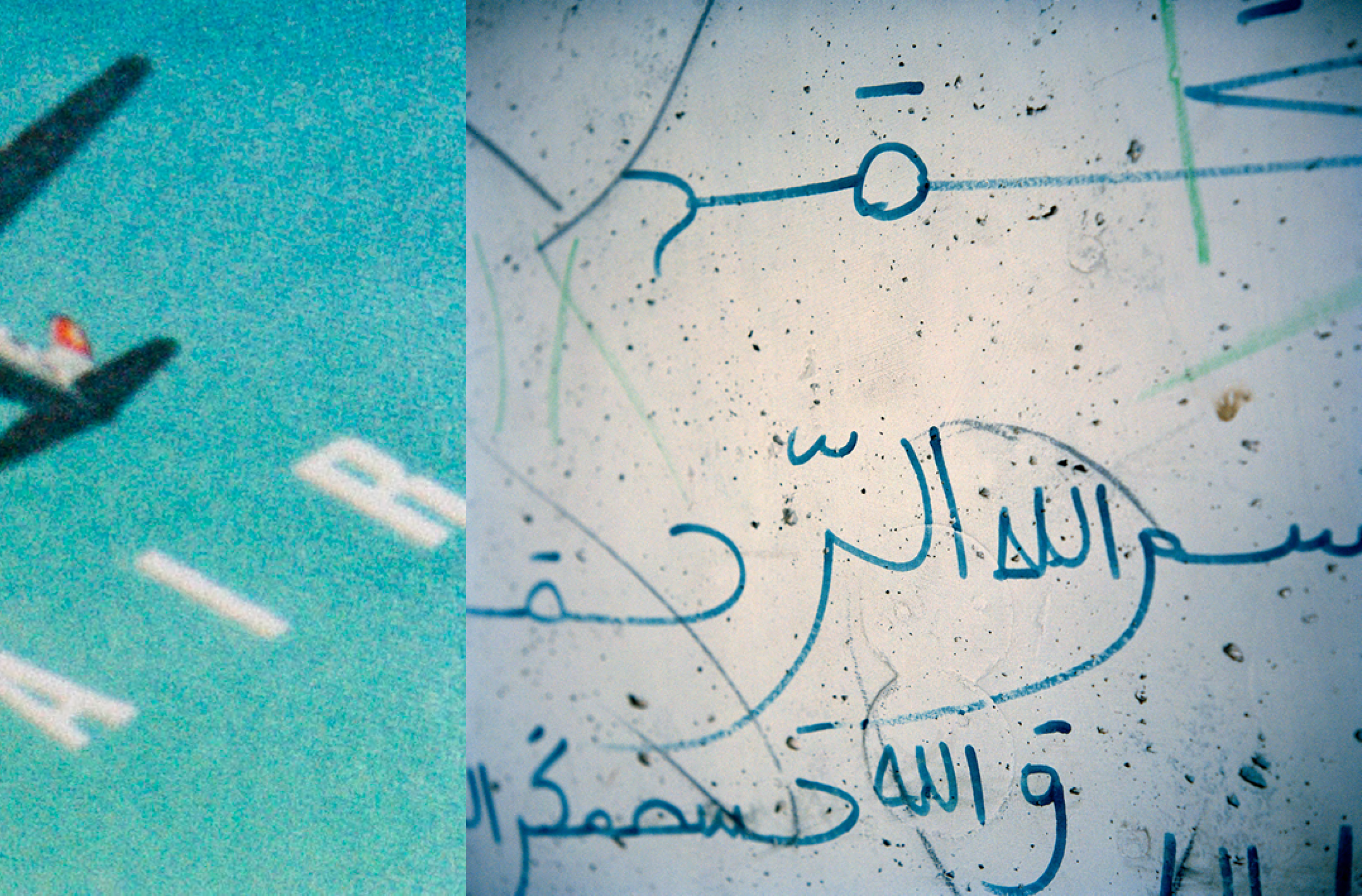

Thus, some of these car parks became temporary homes for people on the move. One was used to create a camp filled with containers, managed by the Red Cross. Another parking structure especially used by frontalieri was occupied by activists and migrants with tents placed on its ground level.27 I visit it on a Sunday afternoon. It is pretty empty. A visible trace of these events remains on a wall protected by two high metal fences, put up by the municipality after clearing the area to prevent the new settlement of people on the move.28 The trace consists of handwriting on the rough concrete parking lot wall (Fig. 14). I get closer and look, trying to decipher the overlaying signs. I do not know what they mean. I take a photograph of those signs, creating a trace of a trace. Several months later, I show that picture to an Arabic-speaking student at the university. He tells me that there is something in the writing that has to do with God, perhaps a verse from the Koran, but he does not completely understand. It makes him feel that in that situation someone still had hope for the future, he tells me.29

As I arrange my notes and the photographs collected so far, I remember when I spoke to a Swiss worker from the industrial area during one of my first visits. She was one of the few Swiss workers in an environment mostly peopled by Italian border commuters. I asked her if she ever crosses into Italy. She said she does so to go to restaurants or meet her colleagues. The border also provides opportunities for meetings. Like a dual element, the border unites and separates.30 She also says she crosses into Italy when she wants to go to the sea further south, since there is no sea in Switzerland. I also keep on moving from south to north, from north to south, and back, around the border landscape. I am aware that mine is a privileged position, that of a white female with a European passport who can easily pass across that line.31 In all those times that I crossed the border, no one has ever asked to check my documents.

At times, my motion seems meaningless. At other times, I feel like I am starting to get to know some of the dynamics of the places. Then the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic limits me because that simple act of crossing becomes impossible. The border is sealed due to health prevention measures. Unable to go out of my house, I start browsing for online videos and images connected to the border (Fig. 4). Then, once the strictest pandemic measures are lifted, I can only stay in the Italian area and cannot cross the border. I get in touch with a migrant centre in the Italian border city of Como. It is non-governmental centre, opened and managed by a priest together with a group of volunteers and activists.32 Don Giusto decided there needed to be some welcoming places during the “crisis” of 2016.

I go to dinner at the centre several times. Dinner, the priest explained to me, is the time for people at the centre to get together. I can ask questions if I want, he adds, not as a researcher interviewing with a notepad and a pencil, but rather as a person talking to others. The men have dinner in a common room, while the women eat in another space, where they can accommodate their children’s needs. In all my visits to the centre, I never come to meet any of the women. The volunteers told me that many women on the move are victims of trafficking or other forms of violence; hence they are very cautious of the people they come across, even the centre activists themselves.

I chat with those I meet in the common room. I do not take any photographs. I feel that the gesture would be an invasion of their space. I am afraid that a dynamic of Othering would be established, as described by those who discussed the camera as a hegemonic tool.33 I am thinking, for instance, of Susan Sontag who spoke of the camera as a “predatory weapon” and of photographs as “trophies” that demonstrate the ability and quickness of the shooter.34 To avoid falling into that trap would require spending more time in the place than is at my disposal.

I take some walks that retrace the crossing itineraries linked to various border stories that I have collected through research and encounters. I establish the starting point, the endpoint, and the in between. I remind myself to pay attention to the edges, the limits, and the signs that I may encounter. There is something performative in them. These times, I take my camera with me. On one such walk, I go back to the border woods. I know that there, as some people I met in Como told me, some people move with the light of dawn, trying to cross while remaining invisible. Someone told me about waking up at dawn and walking for five hours to get to a train station further into Switzerland and less close to the border, where perhaps there are fewer checks on documents.

I know I am running out of time. I walk different paths. I walk in the night, but not alone. I ask someone to accompany me (Fig. 3). I follow the temporality of the border, because precisely in those hours of darkness many of the movements that I am aware of seem to take place. I take some silent night photos, where not much can be seen, but where the dark light seems somehow more appropriate, compared to the full and clear day. While considering the potentiality of photographs to give a glimpse of what is not visible, Hilde van Gelder stated that some photographs can suggest that hidden temporality which Javier Marías described as the “dark back of time.”35 That is, a time that has been but that is no more. Through such photographs, “a time might be felt that once existed in all its full potentiality, as if the photograph somehow is still pregnant with the unrealized possibilities of that temporality or, at least, bears its traces.”36

Some paths have been shaped by the crossing of people who use these woods to run or simply walk. I know there are some old smuggling routes that people walked to take goods into and out of the two countries by hiding them under their dresses or carrying them in handmade rucksacks. They also embodied the border. I check some of these paths, moving to other places around the border landscape. One evening I am back again in the woods where flowers used to be picked by the women working in the shirt factory of the border area. In the light of the barely visible, I spot some glares at the edge between the trees and the road. Compelled by a sudden fear, I get closer to check what these are. A group of fireflies lingers in the grass, close to the ground (Fig. 2). These are small luminescent insects that appear at the margins of greenery in countryside areas at dusk, at that moment when the light is going down because the sun has set, but you can still perceive the contours of things with your eyes. I had never seen live fireflies before, but I had read about them.

In 1975, Pier Pasolini, in a renowned article published in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, wrote about their disappearance in the post-war Italian panorama while considering the ongoing change of landscape due to the ongoing industrialisation that was transforming Italy.37 While fireflies were disappearing, not only was the physical landscape changing, but also the society. The peasant-artisan class was also vanishing in an increasingly industrialised reality. In his text, the disappearance of fireflies is a metaphor for the disappearance of certain values in the society of consumption, within a larger reflection on the persistence of fascism in the post-war panorama. His writing, unlike a previous youthful text of 1941 in which he mentioned to a friend with enthusiastic astonishment a first encounter with fireflies, is steeped in pessimism.38

Years later, Georges Didi-Huberman wrote a response to Pasolini’s thoughts, discussing fireflies as lights of survival, alluding to forms of resistance whose traces may remain in the registered lights of photographs. Fireflies become a metaphor for images that allow us to imagine “in spite of all,” helping us to rethink our model of hope.39 Fireflies, notes Didi-Huberman, moving slowly and emitting a faint light, draw a constellation, as “the Past meets the Present to form a glimmer, a flash, a constellation in which some form for our very Future suddenly breaks free.”40 The word “constellation” may recall Walter Benjamin who, in the prologue to The Origin of German Tragic Drama, stated that ideas are to objects as constellations to stars.41 Constellations are not objective but are human constructs that interpret physical elements that exist as separate points. In the context of artistic practices, the concept of the constellation also recalls the assemblage of different materials – such as photographs and words – single elements that take on a new meaning through their relationship, making figurative constructs that interpret what is visible there in otherwise seemingly unrelated elements.42

Here, with these words, I try to recreate some meaning from this assemblage of photographs, traces of the complexity of the border landscape and its dynamic existence, between visibility and invisibility, as well as of forms of resistance to borders’ binary divisions (Fig. 4). Some meanings seem to remain concealed in the images. In the end, I am left with a firefly image, in the literal sense of a survival image, an image charged with symbolic and synthetic meaning: it is one of the very few surviving frames of a documentary film of 1928 now entirely lost, which the author himself tried in vain to find until his death.43 The documentary, titled Dalla montagna al piano [From the mountain to the plain] and shot by Armin Berner, was dedicated to women’s labour in Canton Ticino and was filmed right before the economic divisions of the border were so clearly crystallised. The frame shows women picking lilies of the valley.

At the feet of a group of women, you can see those flowers typical of pre-Alpine areas, which belong to both sides of the border, that are now slowly disappearing due to the urbanisation of the area. It became illegal to collect these flowers because of a law put in place to protect them, but some women remembered they would still go. “Andavamo di sfroso” [we went as smugglers], they say in the audio interview.44 The words “di sfroso” [as smugglers] are specific terms of this border area, one of many such dialect words that remain difficult to translate. They point to the petty trade around borders, that set of everyday activities resistant to the border. In April 2021, I pay one more visit to the area. I meet a lady in the border trees, now blossoming with white flowers. She gives me a bunch of lilies of the valley as a present. I dry the flowers and keep them.

Once home, I look back at this embodied exploration of the borderscape, whose objective was to provide an alternative representation to the stereotyped and state-centric view of the border as a static line. I feel it has brought out some places that are strongly connoted in the borderscape, on a physical as well as a symbolic and imaginative level: the border factories, sites where the border is produced and reproduced; the places of reception for people on the move, often sites of stasis because of the border filtering functions; the parking lots and stations, sites of junction of trajectories of crossing; and then some liminal spaces, natural areas where freedom of movement seems to be possible, such as the border woods of the flower harvesting.

When I talk about the symbolic and imaginative level, I am referring to what Henri Lefebvre defines in The Production of Space as “space of representation,” a lived space with which the inhabitants associate specific symbols and mental representations.45 For example, here emerges a space of representation related to the border woods, which is dual. On the one hand, the woods can be associated with a slightly romantic and nostalgic vision of space, linked to the forests’ past use for smuggling or agricultural work, now rarely present. In such visions some of the functions of the border seem to be challenged or even to disappear, as in the narration of the flower picking and its associated images.

On the other hand, there is a surveillance vision associated with the woods, which also translates into a specific visuality, such as that of the drones used to patrol the border. Through thermal cameras capable of identifying the presence of bodies according to the temperature difference, drones produce specific patrolling images shot from above. Some inhabitants I met in the woods told me about hearing the sounds of drones flying over their homes at night, when they were probably checking for unauthorised border-crossers. I have decided not to replicate here this visuality of control, while collecting border photographs that are often visually banal and weak. But, even if the border is not clearly visible in such photographs, it is still associated with them, just like its dynamics may be invisible in space, but are always acting.

In both cases, the woods appear as a space for the “out of laws,” who may move in it almost like contemporary Robin Hood, but the perception one has of this space of representation greatly depends on their positionality in the borderscape and the rights of inclusion they do or do not have in it: inhabitants, people on the move, and workers, all have different ones. While the discursive representation of this travelogue explores in practical terms an embodied way of researching a border area, it also helps to identify where to act on it. In these key points of the borderscape, design disciplines could intervene to make it a more inclusive space for all types of border dwellers. It is also an action in itself, a borderscape-ing that contributes to re-shaping the border.46

This article is the result of four-years’ Ph.D. research on forms of representation of the Swiss-Italian border area between Lombardy and Ticino. The research employed different methods, while moving along the border between different disciplines, namely Urban Studies, Art History, and Practice-Based Artistic Research. Its aim was to investigate non-hegemonic forms of representation of this borderscape, moving away from the normative point of view of nation-states. In order not to interrupt the narrative flow of the text, which takes the form of a travelogue, I present the research working methods in this ending note.

I focused on spatial practices of border crossing related to cross-border work and migrations, and their visibility or invisibility. First, I studied the literature of border studies around the notion of a “borderscape,” and then the historical and geographical literature connected to the Swiss-Italian area. A careful analysis of information published in local newspapers was a fundamental step forward.47 From these local sources, I gained an overview of the area, which guided the following research on the ground. I proceeded with fieldwork activities as much as possible in the frame of the COVID-19 pandemic. During several visits to the border area, I carried out a series of structured interviews with actors who have an institutional or active role in this borderscape, such as trade unionists who deal with cross-border workers and activists on migration issues in the border city of Como.48 Numerous informal conversations with local residents, workers, and asylum seekers further enriched my knowledge. I scribbled these conversations, together with personal impressions, in a day-to-day notebook.

I then visited specific places in the borderscape following a method that I call “performative travels,” namely because these visits took place according to defined parameters to retrace certain investigated border-crossing practices. With that information, I moved along chosen itineraries defined according to specific temporalities, such as of the night. During these performative travels, I took photographs, thus creating visual representations of the borderscape. I used different analogue cameras that imposed a form of slow and reflective praxis, in medium format and in 35mm for moving situations, both in colour and black and white. I later incorporated in the research other visual materials, such as historical photographs or screen images from videos on the web, which helped bring forward a reflection on other representations besides mine of the borderscape.

The underlying idea of these methods has always been to work on an understanding of the borderscape that combines representation and experience, imaginaries and sceneries, with attention to the socio-political reality of the area, as suggested by the borderscape notion.49 I considered the inhabitants, the places, and the imaginaries associated with them, together with my direct and embodied experience, while collecting visual fragments. The article summarises this process, bringing together a selection of materials from a larger pool. As a travelogue, the article synthesises of both a physical and a speculative movement within the horizon of the border.

A more comprehensive exploration of the themes addressed in this article will be presented in the upcoming book Between the Visible and the Invisible. Photography and Spaces of Imagination in the Swiss-Italian Borderscape (provisional title), scheduled for publication in 2024 by Brill.

1 In Italian the idiom “preciso come un orologio svizzero” [as accurate as a Swiss watch] is used to refer to something or someone extremely precise.

2 Luca Gaeta, “Questioni Di Metodo Nello Studio Del Confine,” Territorio 79 (2016): 79–88. According to Gaeta, this provenance needs to be critically acknowledged. Hence from the outset, I make clear that I move from a specific positionality, that of an Italian scholar.

3 Francesco Careri, Walkscapes: Camminare Come Pratica Estetica (Turin: Einaudi, 2006), 28–35.

4 Gianluca De Sanctis, La Logica Del Confine: Per Un’antropologia Dello Spazio Nel Mondo Romano (Rome: Carocci, 2015), chapter 2.

5 Guido Codoni, Storie Di Ramina. Vicende, Scoperte e Incontri Camminando Lungo Il Confine Tra Mendrisotto e Italia (Pregassona-Lugano: Fontana Edizioni, 2018).

6 Michiel Baud and Willem van Schendel, “Toward a Comparative

History of Borders,” Journal of World History 8, no. 2 (1997): 211–42. In the literature of border studies there are plenty of records on the criticality of maps. Among the most recent ones in the area of art research, see for example Cristina Giudice and Chiara Giubilaro, “Re-Imagining the Border: Border Art as a Space of Critical Imagination and Creative Resistance,”Geopolitics 20, no. 1 (2015): 79–94.

7 I am aware that the reader may expect to see a map that shows the precise location of the places mentioned in this article. Yet precisely because maps are historically the tool through which borders are constructed, I made the choice of not using a map, to encourage an understanding of space that differs from the traditional representation of borders on political maps.

8 Thomas Nail, Theory of the Border (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190618643.001.0001.

9 In the idea of a “boring” border I take up the words used by the geographer Anke Strüver in her study of the Dutch-German borderscape. See Anke Strüver, Stories of the “Boring Border”: The Dutch-German Borderscape in People’s Minds (Münster: LIT-Verlag, 2005).

10 Paraphrasing Adami; Vittorio Adami, “Confine Italo - Svizzero. Volume II – Parte I. Narrazione,” in

Storia Documentata Dei Confini el Regno d’Italia (Rome: Provveditorato Generale dello Stato, 1927), 25.

11 During Fascism, the Italian borders were entirely inspected and re-marked, probably following diffused rhetoric focused on the “protection” of the national territory. Elisa Pasqual, Marco Ferrari, and Andrea Bagnato, A Moving Border: Alpine Cartographies of Climate Change (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019).

12 Thus I put the term “natural” in quotation marks. On the discursive construction of the idea of natural borders, see for example Peter Sahlins, Boundaries. The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).

13 Allan Sekula, “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” in Thinking Photography. Communications and Culture, ed.Victor Burgin (London: Palgrave, 1982), 84–109.

14 Here and in the use of the concept of “aftermath photography” I follow Donna West Brett in her study of photography in the German landscape after 1945. See Donna West Brett, Photography and Place. Seeing and Not Seeing Germany after 1945 (New York, Oxon: Routledge, 2016).

15 Hilde van Gelder, Ground Sea. Photography and the Right to Be Reborn (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2021), 268.

16 Luca Gaeta, La Civiltà Dei Confini. Pratiche Quotidiane e Forme Di Cittadinanza (Rome: Carocci, 2018), 105 (my translation).

17 I am following here a study by historian Paolo Barcella on the birth of cross-border work between Switzerland and Italy. Such protective labour laws were first established in Canton Glarus in 1846 and later extended to the whole Swiss territory in 1877. See Paolo Barcella, I Frontalieri in Europa. Un Quadro Storico (Milan: Biblion Edizioni, 2019).

18 In August 2015, following a European parliamentary question on “social dumping,” Marianne Thyssen stated that “The term is generally used to point to unfair competition due to the application of different wages and social protection rules to different categories of workers” (Parliamentary questions,

27 May 2015, E-008441-15). See EurWORK, “Social Dumping,” May 19, 2016, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/it/node/86806.

19 The data mentioned comes from Ustat (Ticino Statistics Office) reports of 2020, publicly available on their website. See Ustat, “11 Mobilità e Trasporti,” 2020, https://www3.ti.ch/DFE/DR/USTAT/index.php?fuseaction=temi.tema&proId=49&p1=50. Other contextual information comes from interviews with local trade unionists from the Italian trade union CGIL and the Swiss trade union UNiA, which I carried out between 2020 and 2021 as part of my PhD research (Politecnico di Milano and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2018–2022).

20 This conversation took place during my fieldwork in the border area in July 2020. The conversations reported later are mostly from the same period.

21 Audio interview by Silvia Lesina Martinelli, I Boschi Di Stabio, vol. 34, interviste audio e video sulla Stabio di una volta, 2015, Museo della Memoria della Svizzera, https://museodellamemoria.ch/interviste/i-boschi-e-i-mughetti. Similar information was also shared during informal conversations with people I met in the border area during my fieldwork in July 2020.

22 Literally, “will be satiated with bread.”

23 The notion of crisis, when linked to migrations, has often been criticized, which is why I use quotation marks here. According to Federica Mazzara, migrations are not crises because they are not special events, they are cyclical dynamics that repeat themselves. See Federica Mazzara, “Subverting the Narrative of Lampedusa Borderscape,” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 7, no. 2 (2016): 135–47, https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc.7.2.135_1. I use this term to point to how these specific events are referred to in the local media of the Swiss-Italian border area.

24 I follow Hilde van Gelder on the use of the expression proposed by Amnesty International. See van Gelder, 206.

25 Dublin III EU-regulation of June 26, 2013. The country of the first entrance into Europe must handle the request for political asylum for those entering the union illegally, independently of the asylum seekers’ will to travel to a specific European country. See Aandine Scherrer, ed., Dublin Regulation on International Protection Applications. European Implementation Assessment, European Parliamentary Research Service, 2020.

26 To get registered in the European database EURODAC, irregular people on the move are photographed and their fingerprints are collected within 48 hours of arrival in a European country. Thus, their identification passes through the body.

27 The sites mentioned correspond to the car park in Via Regina Teodolinda and the multi-story parking silo val Mulini in Como, Italy.

28 “Como, in Val Mulini Recinzioni Anti Migranti.” La Provincia di Como, December 15, 2017. https://www.laprovinciadicomo.it/stories/como-citta/como-in-val-mulini-recinzioni-anti-migranti_1264629_11/.

29 Conversation with Yousef Ali Abuzeid in November 2022 at Politecnico di Milano.

30 Gaeta, La Civiltà Dei Confini. Pratiche Quotidiane e Forme Di Cittadinanza.

31 On “white privilege,” see Alessandra Ferrini’s reflections on entering Italian colonial archives as a person who identifies as white. Alessandra Ferrini, “(Re)Entering the Archive: Critical Reflections on Archives and Whiteness,” From the European South 6 (2020): 137–46.

32 The centre is embedded in the Parrocchia di Rebbio in the border Italian town of Como. I spent some time there during fieldwork carried out in July 2020. I was also in contact with the Osservatorio Giuridico per i Migranti, an association that safeguards the rights of migrants in the area.

33 The literature on the camera as a hegemonic tool of representation to “capture” others is vast. For example, Vilém Flusser compared photographers to hunters. See Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography (London: Reaktion Books, 2000), 33.

34 Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1977), 14.

35 Van Gelder, 7.

36 Van Gelder, 77.

37 Pier Paolo Pasolini, “‘Il Vuoto Del Potere’ Ovvero ‘l’articolo Delle Lucciole,’” Corriere Della Sera, February 1, 1975, https://www.corriere.it/speciali/pasolini/potere.html.

38 Georges Didi-Huberman, Survival of the Fireflies, trans. Lia Swope Mitchell (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 5.

39 Didi-Huberman, Survival of the Fireflies. The expression “in spite of all” refers to another text by Didi-Huberman, namely Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz trans. Shane B. Lillis (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

40 Didi-Huberman, Survival of the Fireflies, 30.

41 Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (London: Verso, 2009).

42 On the use of the term constellation in artistic practices, I refer here to Jean-Christophe Royoux’s writings on the work of the Swiss and Italian artist Marco Poloni. Jean-Christophe Royoux, “Constellations. Manières de Faire Des Mondes,” in Day after Day: Kunsthalle Fribourg: Fri-Art: 2003–2007 (Fribourg: Kunsthalle Fribourg, 2007), 28–43.

43 The image is reproduced in Guido Codoni, Storie Di Ramina. Vicende, Scoperte e Incontri Camminando Lungo Il Confine Tra Mendrisotto e Italia (Pregassona-Lugano: Fontana Edizioni, 2018), 47. The documentary was produced for the Swiss Exhibition for Women’s Work organized by the

Federation of Swiss Women’s Associations in Bern, called SAFFA Schweizerische Ausstellung für Frauenarbeit.

44 Lesina Martinelli, xx.

45 Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991).

46 Brambilla.

47 Key sources have been the online newspaper Corriere del Ticino, Tio.ch, Ticinonews.ch, La Provincia di Como, Il Giorno-Como.

48 For example, trade unionists from the Italian CGIL trade union and the Swiss UNiA, and Italian volunteers and workers from Osservatorio Giuridico per i Migranti in Como and the association Como Senza Frontiere.

49 Chiara Brambilla, “Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept,” Geopolitics 20, no. 1 (2015): 14–34.

Nicoletta Grillo

University of Hasselt, Faculty of Architecture and Arts

The national boundary line that separates Italy and Switzerland is today highly dematerialised and mostly invisible. Yet it continues to exist as a “borderscape,” reproduced by a series of crossing practices such as cross-border work and migration, and by their associated imaginaries. Based on oral history, photography, and performative walks, this essay gives a first-person account of how this border is kept alive or contested by those practices that routinely cross it. The starting point is the story of women workers employed in a manufacturing factory in the border area who used to go to the border woods to harvest flowers. Moving between border factories, workers’ parking lots, migratory trajectories, and smuggling routes, the essay tests on the ground the notion of a borderscape at the interception of experiences and representations.

Borderscape; Switzerland and Italy; Photography; Cross-border work; Migration trajectories; Imagination.

1 Panorama on Lake Lugano from the Italian side. The Swiss-Italian border cuts through the lake. Lanzo d’Intelvi, November 2019. Nicoletta Grillo.

2 Fireflies in the woods on a road that leads to the Swiss-Italian border. Bizzarone, May 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

3 Walking along the path that connects the Italian village of Erbonne and the Swiss village of Scudellate, which is often associated with smuggling in the local memory. Scudellate, July 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

4 Photograph of a detail of a screen showing an image of a protest against the closure of the border organised by people on the move in Como in 2016. The image was saved on the author’s computer in March 2020, probably from the ANSA news agency, which later disappeared from the web. The colours have been inverted to make faces less recognisable. Nicoletta Grillo.

5 Driving towards the Swiss-Italian border. Probably Bizzarone, July 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

6 Remains of the ramina, the wire fence that once closed the border. Uggiate Trevano, January 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

7 Detail of an archival image showing a women shirtmakers’ strike of 1941 in Mendrisio to ask for a collective labour contract. Scanned from Guido Codoni, Storie Di Ramina. Vicende, Scoperte e Incontri Camminando Lungo Il Confine Tra Mendrisotto e Italia (Pregassona-Lugano: Fontana Edizioni, 2018), 24, reproduced with the permission of the publishing house. Unknown photographer.

8 Inside a contemporary factory in the border area (the photograph has been significantly cropped to make the place anonymous; due to privacy agreements it cannot be published or shown). Mendrisio, July 2021. Nicoletta Grillo.

9 Portrait of A., a former smuggler encountered in the border area (the photograph has been cut to make his face unrecognisable). Italy, July 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

10 Woods on the Swiss-Italian border. Bizzarone, July 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

11 Archival image of Camiceria Realini shirt factory. Stabio, Switzerland, unknown date (ca. 1940s). Scanned by the author from a physical print provided by a local resident. Unknown photographer.

12 An owl from the collection of the ethnographic museum of Val Bregaglia. Ciäsa Granda, Stampa, August 2019. Nicoletta Grillo.

13 Photograph of a detail of a historical poster of the Swiss airline. May 2021. Nicoletta Grillo.

14 Writing on the wall of a parking building formerly occupied by people on the move. Autosilo Valmulini, Como, July 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

14 The beginning of the industrial area of Stabio next to the border. Stabio, July 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

15 Inside Maxim brothel at the Como/Chiasso border. Chiasso, September 2020. Nicoletta Grillo.

16 Frame from a 35 mm documentary on women labor in Ticino Dalla Montagna al Piano (1928), by Armin Berner. Unknown frame minute. Scanned from Guido Codoni, Storie Di Ramina. Vicende, Scoperte e Incontri Camminando Lungo Il Confine Tra Mendrisotto e Italia (Pregassona-Lugano: Fontana Edizioni, 2018), 47, reproduced with the permission of the publishing house. Armin Berner.

Nicoletta Grillo is an artist and researcher based in Brussels and Milan. After studying architecture and photography, she completed a theoretical and practical PhD on photographic counter-representations of border landscapes (Politecnico di Milano and KU Leuven). Her works incorporate photographs, performance practices and narratives, in audio or written forms, to open new spaces of imagination for marginal landscapes and subjects. She is an Assistant Professor in Visual Arts at the University of Hasselt.

REFERENCES

Adami, Vittorio. “Confine Italo - Svizzero. Volume II – Parte I. Narrazione.” In Storia Documentata Dei Confini Del Regno d’Italia. Rome: Provveditorato Generale dello Stato, 1927.

Barcella, Paolo. I Frontalieri in Europa. Un Quadro Storico. Milano: Biblion Edizioni, 2019.

Baud, Michiel, and Willem van Schendel. “Toward a Comparative History of Borders.” Journal of World History 8, no. 2 (1997): 211–42.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Translated by John Osborne. London: Verso, 2009.

Brambilla, Chiara. “Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept.” Geopolitics 20, no. 1 (2015): 14–34.

Brett, Donna West. Photography and Place. Seeing and Not Seeing Germany after 1945. New York, Oxon: Routledge, 2016.

Careri, Francesco. Walkscapes: Camminare Come Pratica Estetica. Torino: Einaudi, 2006.

Codoni, Guido. Storie Di Ramina. Vicende, Scoperte e Incontri Camminando Lungo Il Confine Tra Mendrisotto e Italia. Pregassona-Lugano: Fontana Edizioni, 2018.

“Como, in Val Mulini Recinzioni Anti Migranti.” La Provincia di Como, December 15, 2017. https://www.laprovinciadicomo.it/stories/como-citta/como-in-val-mulini-recinzioni-anti-migranti_1264629_11/.

De Sanctis, Gianluca. La Logica Del Confine: Per Un’antropologia Dello Spazio Nel Mondo Romano. Roma: Carocci, 2015.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz. Translated by Shane B. Lillis. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Survival of the Fireflies. Translated by Lia Swope Mitchell. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

EurWORK. “Social Dumping.” May 19, 2016. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/it/node/86806.

Ferrini, Alessandra. “(Re)Entering the Archive: Critical Reflections on Archives and Whiteness.” From the European South 6 (2020): 137–46.

Flusser, Vilém. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaktion Books, 2000.

Gaeta, Luca. La Civiltà Dei Confini. Pratiche Quotidiane e Forme Di Cittadinanza. Roma: Carocci, 2018.

Gaeta, Luca. “Questioni Di Metodo Nello Studio Del Confine.” Territorio 79 (2016): 79–88.

Giudice, Cristina, and Chiara Giubilaro. “Re-Imagining the Border: Border Art as a Space of Critical Imagination and Creative Resistance.” Geopolitics 20, no. 1 (2015): 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.896791.

Grossi, Plinio. Il Ticino Dei ’20. Lugano: Fontana Edizioni, 1996.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

Lesina Martinelli, Silvia. I Boschi Di Stabio. Vol. 34. Interviste audio e video sulla Stabio di una volta, 2015. Museo della Memoria della Svizzera. https://museodellamemoria.ch/interviste/i-boschi-e-i-mughetti.

Mazzara, Federica. “Subverting the Narrative of Lampedusa Borderscape.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 7, no. 2 (2016): 135–47. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc.7.2.135_1.

Nail, Thomas. Theory of the Border. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190618643.001.0001.

Pasolini, Pier Paolo. “‘Il Vuoto Del Potere’ Ovvero ‘l’articolo Delle Lucciole.’” Corriere Della Sera, February 1, 1975. https://www.corriere.it/speciali/pasolini/potere.html.

Pasqual, Elisa, Marco Ferrari, and Andrea Bagnato. A Moving Border: Alpine Cartographies of Climate Change. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

Royoux, Jean-Christophe. “Constellations. Manières de Faire Des Mondes.” In Day After Day: Kunsthalle Fribourg: Fri-Art: 2003-2007, 28–43. Fribourg: Kunsthalle Fribourg, 2007. https://doi.org/10.3917/mult.079.0144.

Sahlins, Peter. Boundaries. The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Scherrer, Aandine. Dublin Regulation on International Protection Applications. European Implementation Assessment. European Parliamentary Research Service, 2020.

Sekula, Allan. “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning.” In Thinking Photography. Communications and Culture, edited by Victor Burgin, 84–109. London: Palgrave, 1982.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1977.

Strüver, Anke. Stories of the “Boring Border”: The Dutch-German Borderscape in People’s Minds. Münster: LIT-Verlag, 2005.

Van Gelder, Hilde. Ground Sea. Photography and the Right to Be Reborn. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2021.