A Tinder Lover’s Discourse

Marilia Kaisar

This essay is an attempt to combine personal experiences and data with research on interfaces and software theory to reflect on personal Tinder experiences and speculate on contemporary desire in the age of dating applications. Blending poetic personal narratives with scholarly readings on software, desire, and the virtual, this essay uses a critical lens to examine the repetitive motions of swiping, messaging, and dating. Extending Roland Barthes’s lineage, the amorous subjectivity embedded in the Tinder swiping motions is a solitary one, trying to attach to a constantly moving, eternally replaceable object of desire.

Keywords: Tinder, autotheory, desire, dating applications, pleasure

I Dated Them All: An Introduction

“It is a lover who speaks and says...”[1]

I dated them all.

The Nigerian prince who dined me at Michelin-starred restaurants,

got me VIP tickets for theatre shows, and wanted to write a script for a web series

but was always late on dates, and one day I found his ex’s period stains on the sheets.

The hip-hop musician who had a nipple fetish and had lost his dad a year ago.

The designer who owned a distribution company but sweated a lot,

little tears of sweat dripping from his forehead and a neck that looked like snakeskin.

The security guard who painted beautiful sketches and had a heart full of gold

but was getting trained to join the army to pay off his student loans.

The creative writer who worked at bars and tried all the drugs

but wanted me to spoon him as he fell asleep.

The intellectual from Virginia who hated condoms and convinced me

that fucking him with a condom would be an act of racial discrimination.

The vegetarian spoken-word poet who wrote lesbian romantic novels,

worked in a spiritual bookshop, and drove me into the California highways

while smoking cigarettes, but was a bit too sweet for my taste.

The biologist who studied bats and loved butts but was poly,

who gave me edibles, took me to weird film screenings, and took my tears away when I failed.

The special effects guy who told me he was trying to be a feminist,

but it takes hard work to undo the patriarchy’s hardwiring, so I gave him my body as praise.

The Canadian guy who graduated film school and was my regular booty call,

who, when I saw him a year later, was working as an editor for porn.

The black undergraduate student who kept telling me he was from China

and had anal with me without kissing so as not to cheat on his girlfriend.

The Mexican Jewish writer with a body filled with colourful ink whom I almost fell for,

who only took me on a date per season—summer, spring, fall, winter—

walking around New York and having deep conversations on everything and nothing.

The Greek American guy who spoke no Greek and kissed really badly

but dared to tell me his yiayia makes a better spanakopita than me.

The British IT guy who was also a personal trainer with shiny, chiselled abs,

who ordered egg sandwiches and sweet coffee in the morning

and then spent the day with me fucking and watching football.

The hairdresser in New Orleans who had been in prison for three years

because he was selling heroin to build a house in Puerto Rico and feed his baby daughter.

The architect who had a Jehovah’s Witness son and a pet dog he regularly electrocuted

to stay off his bed, who always bought me food and fucked me in a dominant way

but never spoke too much, never shared enough, never opened his heart.

The arts educator who took me to art museums and walked by my side all over New York,

who shared his food with me in restaurants but then vanished in the blink of an eye.

The white comedian who failed to make it in LA and asked me to pay for my drinks.

The guy who worked at Spotify, and we didn’t work out;

we met in a brewery, he brought me a gift and offered it to me, smiling,

and we had a few drinks as he listened to the pains of my life.

The mixed-race robotics guy who had lived in China

and used a 3D-printed bike as a means of transport.

The DJ from the Philippines who said my armpits smell like onions

and always came to my bed asking, “Did you miss me?”

before he vanished into the dark New York nights.

The male ballerina who waited tables at an Indian restaurant.

The architect from Egypt who drank protein shakes and lifted weights,

trying to shed the weight that had been covering him his entire life.

The web developer from Haiti who had a condo in West Village, gave really good head, and asked Siri to turn off the lights when it was time to go to sleep.

The guy who had his nose massacred by a bulldog, but he still trusted dogs.

The homeschooled boy who got bullied in high school, gave girlfriends his credit card,

and filled his muscles with tattoos just to feel desired and loved again.

The Jamaican UPS guy who had the widest, whitest smile I have ever seen,

who got me artisan beer and took me to watch the waves of the Pacific

while telling me about his love of smoked meat, rocks, and metals.

The Californian music producer who had never missed Coachella,

loved Vampire Weekend and took beautiful photos of BLM protests.

Others paid it all.

Others split it

Others fucked well.

Others kissed me.

But with all of them, without exception,

we shared the hope of a connection.

that maybe the networks would fulfil their purpose

I dated them all, only to figure out

how alone we all are

enslaved by our smartphones,

estranged from our nows.

Thousands of miles from my home and family, I started writing this poem, which might resemble a lover’s list, during a period when, single and alone in New York, I found myself addicted to Tinder after a devastating breakup. As a new transplant to the United States, the nights were solitary, since after 5 p.m. contact with friends and family in Greece was impossible, so I went on and swiped, swiped and dated, along with many other New Yorkers. I do not intend in any way to say that my personal lived experience is a special or extraordinary one, but it is the experience of a foreigner in the metropolis who uses Tinder to connect, reach out, and be with others, whoever they may be. This lived experience, my own embodied entanglement with my smartphone device, the networked connections Tinder provided me with that actualised into real dates in New York City, are what pushed me to start reading and writing about Tinder.

The paper has the following structure: In the first section, I discuss the fragments of personal Tinder poetry and the first-person address I use and the relationship of this project to autotheory and its attempts to create a self-reflexive analysis of the Tinder interface. In this section, I also discuss how Tinder allows the development of a specific empowered subjectivity that is forced into a binary transaction with the potential matches provided by the application. The second section of the paper explores how the application’s Messaging function allows a feeling of ambient intimacy and creates a moving object of desire. In the third section, I look at Tinder’s relationship to enjoyment, pleasure, and entertainment and the gamification of dating and desire. I see a clear lineage from Roland Barthes’s amorous subjectivity, which attempts to confront an absent other and the movable object of desire that is fostered within Tinder.

Roland Barthes structures his book A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments around fragments of discourse, which he calls σχήματα (schema), amorous episodes where the lover’s subjectivity is caught at a standstill.[2] For Barthes, the lover’s discourse is one of extreme solitude, a discourse spoken by thousands but warranted by no one. In the fragments included in the book, the subject speaks through itself, amorously confronting the other, the loved object, who does not speak. This discourse is not dialectical but captures the amorous subject within different moments of what Barthes calls a “linguistic outburst,” a moment when the figure of the lover explores and vibrates. Those moments can be experienced at different intervals within each love story, but together they structure this book of a lover speaking amorously within the self. Barthes’s amorous solitary subjectivity resembles the solitary repetitive swiping motions of the Tinder lover immersed within the ambient intimacy of the application. Therefore, I use my personal narratives as linguistic outbursts that are then used through the analysis to form Tinder subjectivities through the interface and the haptic movement of the swipe.

Tinder allows the user to become a powerful, desiring subject, sorting through an infinite pool of matches while also defining the self as an object of someone else’s desire, an object for the other user’s gaze. The process of intimate communication through written language (messaging) remains steady as the object of desire changes details and faces. Matches become easily surpassed and replaced when the connection fails. One match becomes another, but the cycle of swiping, matching, messaging, dating, and disappearing remains unchanged. The Tinder circles leave behind them traces of data, a pattern demonstrating each user’s romantic history. Using autopoiesis and the subjective, I attempt to explore this circle of affecting and being affected and what those repetitive patterns reveal about contemporary desire.

I see my approach here as an analysis or theorization of my own battles with the Tinder world. By studying the intentions of Tinder’s creators, the gamification of desire, and the functioning and hapticity of the interface, I gradually came to understand my own investment in this dating world, my years-long relationship with the application and its unlimited pool of singles, and how, time after time, the app promised to rescue me from boredom and loneliness, only to bury me deeper in it. Tinder is often analysed from two angles: on the one hand, the academic readings, interface studies, software analysis, and studies of Tinder use through sociological and ethnographic methodologies, and on the other hand, the Buzzfeed articles, testimonies, journaling narratives, poems, and memes from those who experience it daily. The first angle appears to be distanced from reality in order to understand it, while the second almost myopically fails to explore what Tinder means or does. How can the analysis meet the embodied lived experience? And how does Tinder produce an amorous subjectivity? There are two sides to the “I” who speaks here, but both of them are one, and each builds upon the other. So why remove the personal experience from theory, and why not integrate them? Who knows Tinder better than a serial swiper who actually attempts to study the interface while reading Barthes and psychoanalysis on the side? And can this revelation of the intentions and overlapping layers of the subjectivity of the writer within this essay count as autotheory?

Lauren Fournier approaches autotheory as a provocation that integrates the self with theory, producing self-reflective works that challenge theory or the master’s discourses by relating them to embodied lived experience and the subject that produces the theory or writes in relation to the world surrounding them.[3] While Fournier sees the potential of embodied lived experience, Marquis Bey, in his essay “On Lived Experience,” finds the deployment of lived experiences problematic as lived experiences within oppressive systems: Although they are valid, they often do not provide enough analysis of the oppressive system. Extending the thoughts of Bey and Fournier, I intend to create in this essay a space where the embodied lived experience can meet analysis. I use images and screenshots from my own Tinder profile, my memories and narratives of being immersed in the “swipe life,” and my own data that I requested from Tinder, which catalogues in detail how many times I logged on and off the app and how many bios and photographs I altered, silently transcribing my communications with potential lovers. Then, examining the interface and functions of the application, I attempt to understand how Tinder creates an affective, haptic relationship with a movable object of desire and how the contemporary lover experiences this repetitive circulation of swipes, messages, and affects.

The Swipe Makes the Subject

No stress.

No rejection.

Just tap through the profiles you’re interested in, chat online with your matches, [and] then step away from your phone, meet up in the real world, and spark something new.[4]

“So it is a lover who speaks and says...”[5]

Swipe right, swipe left.

Decline or accept.

Text on Tinder.

Text through SMS.

Text ’til there is nothing else to text.

Text on zodiac signs and failures of the past

and what you ate today and how you wear your pubic hair.

Meet and greet.

Fuck and drink.

Release—and then say goodbye.

Vanish.

The line from one point to the next gets cut.

Hours and minutes spent into nothingness.

People you knew and then you didn’t.

Digital lovers vanish into the thin air of pixels.

Spread their existence into networks.

Lost forever.

Trying again to connect new strings, new dots, and new people, form new connections.

A never-ending cycle that ends in loss or disappearance.

Farewell, my digital lovers; you will not be remembered for long.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, “tinder” is a flammable substance or something that serves to incite or inflame.[6] Tinder, first launched in September 2012,[7] is a dating application that incorporates smartphone location and the trademark gesture known as the “swipe” (reflecting the binary decision—yes or no—of whether to date someone). In computing, interfaces can be thought of as the layers between software and hardware, code and device, user and data. For Benjamin Bratton, an application like Tinder is an “interface between the User and his environment and the things within it, aiding in looking, writing, subtitling, capturing, sorting, hearing, and linking things and events.”[8] What Tinder provides is a link between the physical geolocation and the data that overlay this space—in Tinder’s case, the profiles of other singles in the area. According to the location of my smartphone, as well as the age and gender filters set, the app displays all the profiles available in the surrounding area, up to a fifty-mile radius. Tinder filters those people according to the user’s position on the map. Tinder then functions as a filter between me and the world, selecting and feeding me with dating options.

Bratton goes on to define user interfaces as diagrams of possible action, a menu of simulations that, when activated through a user-initiated motion, execute a procedure, resulting in an outcome approximating what was displayed on the menu.[9] Cramer and Fuller explain how a user placed in front of an application’s interface is considered the subject or agent, who has the power to access and interact with computational patterns and elements that describe all possible interactions within the application’s domain[10]. In a sense, the interface limits, outlines, and governs all possible interactions that the user can have and allows the user to see what they can do with the application or software.

In an interview with Time, Sean Rad, one founder of Tinder, says, “We always saw Tinder, the interface, as a game.”[11] As he explains, the whole application was modelled on the idea of a stack of cards, like the sports-card collections we exchanged as children. This time, instead of football players, Pokémon, or witch spells, the cards display potential matches and their personal details. One must interact with the top card by throwing it to one side to reveal other potential matches. If two users reciprocally swipe right, they become a match, and they can move to the Messaging mode to chat. The user’s hand can interact with and manipulate the interface, and its owner gets intertwined, interlaced, entangled, and influenced by the information and experiences to which the interface opens them.[12] Tinder’s interface incorporates different hand gestures, such as tapping, pressing buttons, and, of course, swiping.

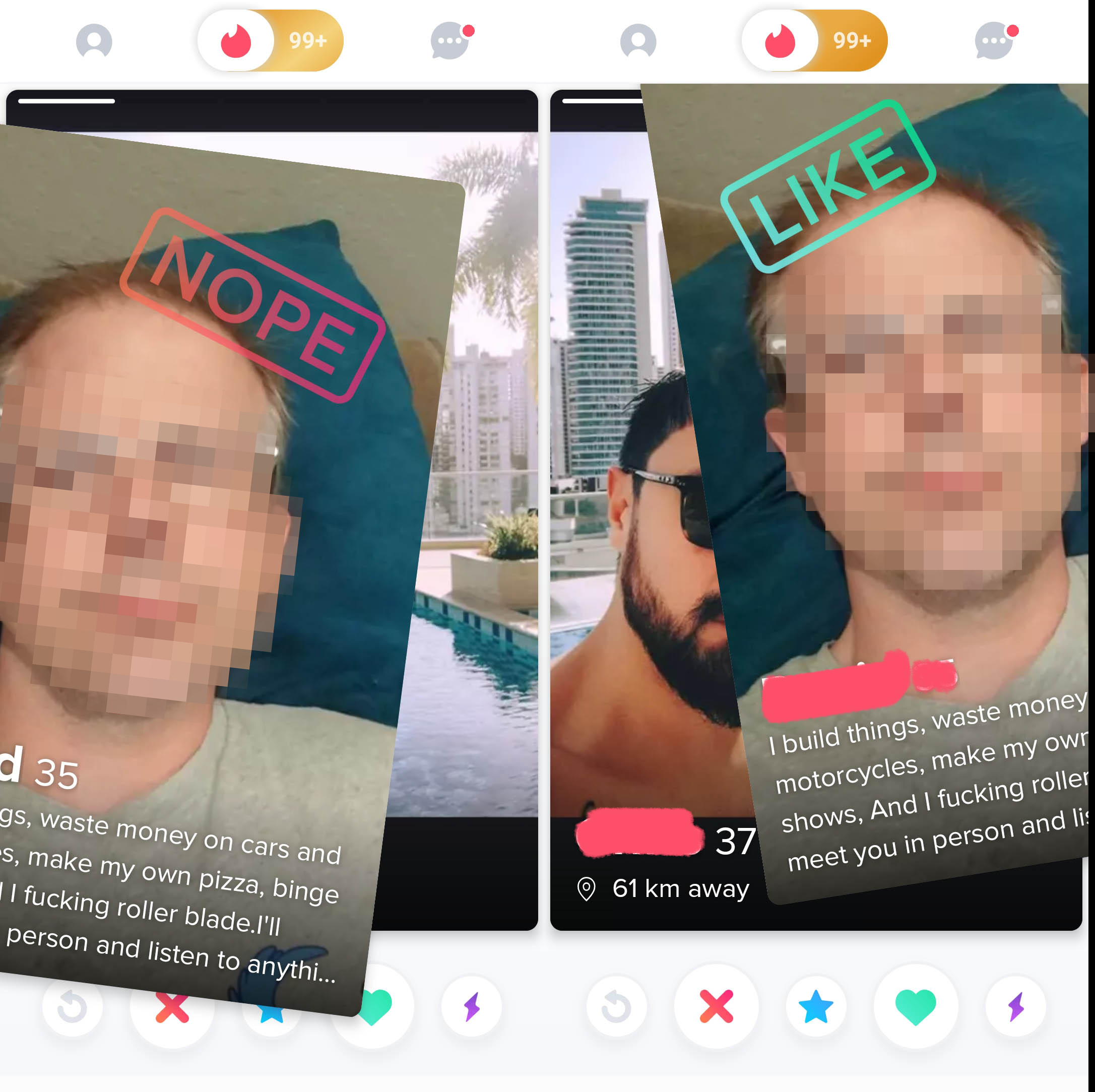

Swiping is a sliding motion of the finger to the right or left on the phone screen, a movement that is determined while simultaneously caressing the device. Each user is allowed twenty right swipes per twenty-four-hour period. In his interview, Rad claims that “the fun activity of swiping, the motion and the reaction, is the main reason why people join Tinder, not their desire to find a potential match.”[13] The act of swiping turns the app into a never-ending game that someone would still want to play even if they weren’t looking for a date. When I swipe left or right, an animation that resembles a seal or stamp appears at the top of the profile, saying “Like” for approval and “Nope” for disapproval. Thus, my swiping decision is credited with an official seal of approval or disapproval (Fig. 1). If I match with someone, a small animation appears saying, “It’s a match. [X] likes you too!” If I swipe left, then the undesirable profile disappears forever as a potential match. Tinder gives me the options; all I must do is decide, judge, and determine who I like and don’t like. This binary transaction between me (the user) and the interface can easily be translated into code.

Fig. 1. A seal of approval. Screenshot from Tinder profile. Created by the author. Accessed 12 Jan. 2019.

According to Søren Pold, “buttons force decisions into binary choices” by transforming the user into a “masterful subject in full control of the situation,” triggering happiness and making the world of information seem accessible and “on the edge of one’s fingertip.”[14] It entails a feeling of commanding and controlling the interface, the finger being able to order the potential matches available in the application. In the controlled environment of an interface, where all possibility is directed by the creator’s design, the user still feels like a strong subject who can make decisions and who becomes the central factor in every interaction. This feeling of power and mastery, however, is carefully crafted and designed.

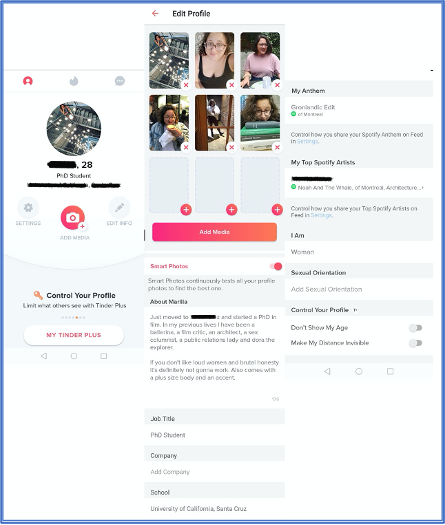

This false sense of subjectivity, which relates to mastery and a power to interact with elements of the outside environment, is also fostered through the creation of a profile that captures my existence in the virtual space. As I log on to the application for the first time, I am asked to use my Facebook profile or phone number to verify my identity. Tinder borrows specific types of information from my Facebook profile—such as age, education, work, and photographs—to start building a basic profile. Unlike old dating applications and services, the data imported from Facebook ensures the validity of the user, guaranteeing that their information is not randomly scripted but actually reflects reality. I can upload up to nine photos and write a personal description of up to five hundred characters to personalise the profile that other users will encounter in the application (Fig. 2). Through this small text I define myself, my likes and dislikes, and my personality, in order to capture the interest of a potential match. I can further individualise my Tinder presence by linking my profile to my Spotify or Instagram accounts. Signing up and creating a profile transforms me into a Tinder profile or card for others to “swipe” through, an object of the collective gaze. At the same time, this profiling also transforms me into a choosing subject with a moving finger commanding the interface.

Fig. 2. Screenshot from Tinder profile. Created by the author. Accessed 12 Jan. 2019.

The “swipe” becomes attached to the Tinder application, and the dating process is redefined by one’s power to use their finger to sort through a seemingly infinite stack of potential partners. The complex process of meeting someone, getting to know them, and asking them out is simplified and transformed into a simple finger movement. The swipe itself, then, is transformed into a unique gesture of swiping and sorting people—one stack for the people you like, another for those you don’t. The choice of whether to date someone is reduced to a binary choice—“Like” or “Nope,” swipe right or swipe left—sorting through as many potential singles as possible, as quickly as possible, solving the problem of dating with the tip of your finger.

Erica Biddle writes that “the perverse pleasure of being subjects to power by participating in its growth fulfils a post-historical yearning for virtual participation.”[15] In Tinder’s world, everyone is a judge in an infinite game of decisions, as well as an object of other users’ desires, participating in a game of choice. Tinder is a never-ending game of transition from masterful subject to object of someone else’s desire. You sort the stack while being sorted, and you judge while being judged. The more matches you get, the more valuable and interesting your profile is. Biddle reads the notion of the haptic as “nonverbal communication and somatic feedback.”[16] The “swipe” is a nonverbal gesture, a haptic movement that takes place on the topology of the screen. When the validation “It’s a match” appears or when my phone buzzes with a new message from an exciting match, I feel the vibrating pleasure of success pings. I have successfully interacted with the interface and sorted potential matches on the screen long enough to receive at last the pleasurable notification that I have matched with another person and can now proceed to the next part of the interaction: Messaging mode.

Ambient Intimacy and Movable Objects of Desire

“So it is a lover who speaks and says...”[17]

It was one of those nights, at a house party,

where you know everyone pretty well,

so you turn to your Tinder matches for a quick fix.

You do know that no one has ever

gone on a good date after 2:00 a.m. or two bottles of wine.

He picked me up in front of the house, and it was really cold, New York in December.

He was a basketball player in Europe, stuck in NYC because of a shoulder injury.

He was waiting to get surgery while missing his game season.

He didn’t want to have a drink at a bar.

We walked around Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn; the streets were empty.

I was on automatic pilot, so somehow we ended up under my home.

In front of my apartment building, he told me he was an orphan.

I gave him an awkward hug.

He insisted on coming upstairs, and I couldn’t say no.

We ended up lying on my bed, sipping my cheap bottle of red.

We fell asleep without ever touching or kissing each other.

The next morning, I woke up, and he was gone.

His presence was replaced with an intense headache.

I checked the app and realized he had unmatched me,

all traces lost, every possible connection vanished.

Just a bottle of opened red and two half-empty glasses on my nightstand.

Lying in my bed alone, I wondered if I had imagined everything.

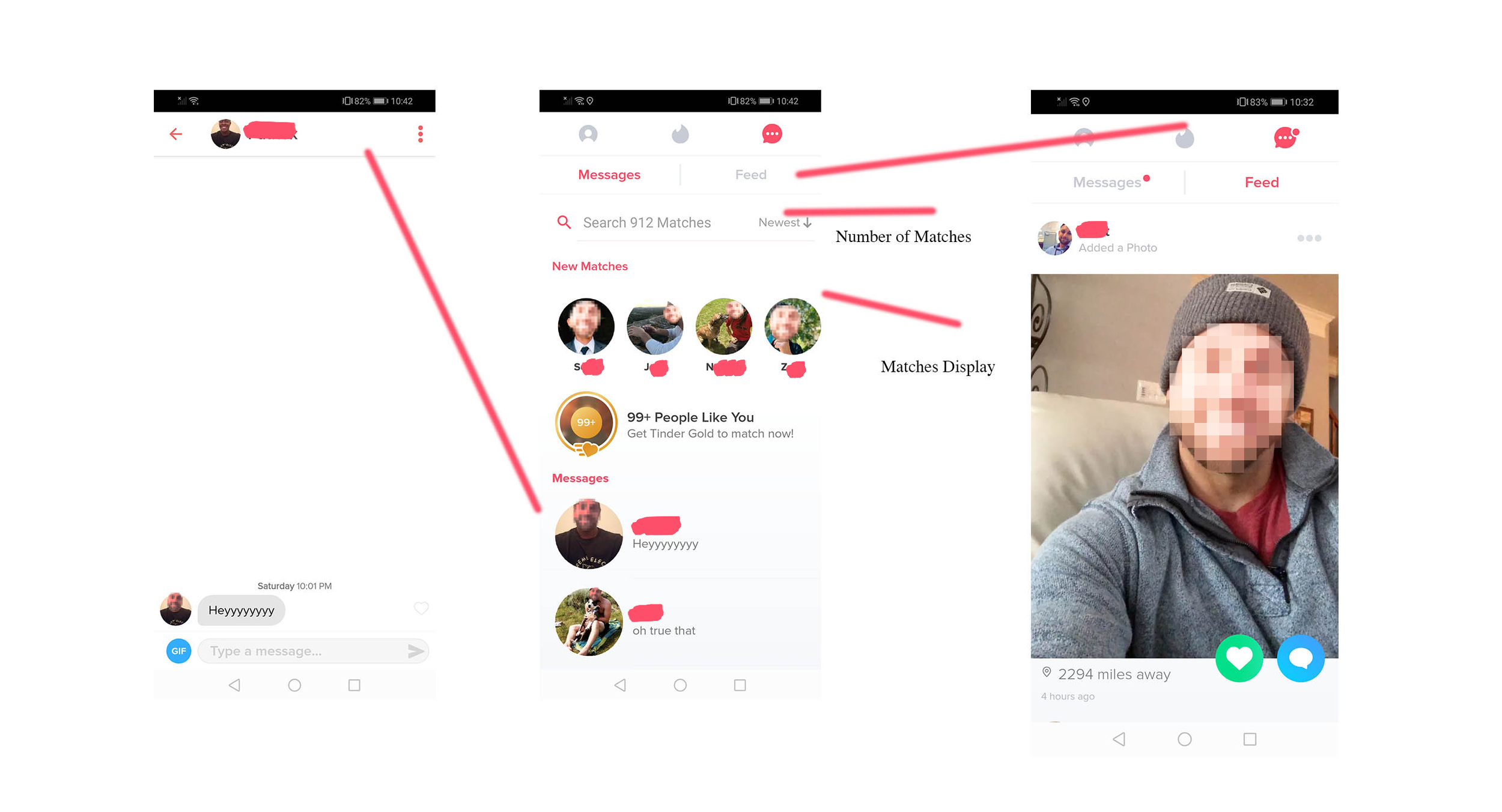

In Messaging mode, users can review and search past matches and initiate a discussion on private chat boards (Fig.3). Messaging with a match allows me to share intimate conversations with an invisible other. As I invest the time to closely read the details of a match’s profile or repetitively message them to determine whether they are dateable, I have a much more personal experience than the initial swipe that led me there. Lisa Reichelt coined the term “ambient intimacy,” which she defined as “being able to keep in touch with people with a level of regularity and intimacy that you wouldn’t usually have access to because time and space conspire to make it impossible”[18] Sharing personal details and fragments of everyday life with a stranger gradually adds value to the relationship and creates a sense of familiarity before going on a date.

Fig. 3. Screenshot from Tinder. Created by the author. Accessed 12 Jan. 2019.

As I am sharing, writing, and chatting with my matches, at any point during the conversation, if I am dissatisfied with the correspondence, I can “unmatch” or be unmatched by them. The unmatch function makes the match disappear forever. The card and messaging history both vanish in the blink of an eye, irreversibly, but the experience is very different when, as I am engaging in an involved and intimate conversation, the other user unmatches me. Suddenly, after feeling the positive vibrations of messages being received as I engage in an involved conversation, the vibrations stop. I return to the app, only to find that my match has disappeared. At times, it seems like I imagined the match; it is like this whole conversation never happened. The time and energy I spent on that match, engaging and sharing information with them, vanish forever, with no trace of their existence. When that happens, I feel violently cut out. I return to Discovery mode to find someone to replace the lost match, but my attempts are often fruitless. What is left is a feeling of emptiness, with my time and energy stolen and the match absent and forever lost.

When writing about absence, Barthes discusses how the lover stays immobile and the object of desire (the match) departs.[19] The match is gone, and I must endure their absence. I remain alone with a memory of our conversation but without any proof of it or any reason for the disappearance. I try to endure this absence by replacing one match with another, displacing the desire I felt with another object where I can place my affection, another situation where I can engage in an intimate discussion. Barthes writes, influenced by or vaguely quoting the Greeks, “But isn’t desire always the same, whether the object is present or absent? Isn’t the object always absent?”[20]

In François Truffaut’s film The Story of Adèle H., we see the female protagonist writing passionate letters to an absent, unresponsive lover. His lack of response is what intensifies her desire and feeds her fantasies of being involved with him. She sees him desiring and flirting with other women, but nothing can turn her away. In The Subject of Semiotics, Kaja Silverman uses Adèle H. and her passionate writing process to explain the primary processes of desire and the function of displacement. The protagonist’s writing routine is an act of affection that relates her to her father but replaces her father as an object of desire with a different man and the act of writing itself.[21]

Adèle’s unreciprocated desire and letter-writing routine are very similar to my experience with the Messaging mode. Every match on Tinder is a constantly replaceable object of desire. What becomes addictive and pleasurable is not the person, nor even the dating process itself. The process of constant correspondence and the abstract feeling of ambient intimacy with a stranger becomes a habit of moving desire and ambient intimacy from one match to the next and to the process as a whole. My addiction to Tinder is evident when I get increasingly used to the constant flow of notifications, messages, matches—the feeling of ambient intimacy, of being able to communicate, of being desired and connected. Like Adèle, I frantically send messages to potential suitors, not seeing them for what they are but rather as a collective public of desire. It is not whom I message per se but the feeling of being heard and the potential for my desire to be fulfilled. Erica Biddle writes,

There can be no permanent satisfaction of desire, only the creation of dissatisfaction following a temporary high. The carrot the Internet offers is the pleasure of participation, the fantasy-generating element, the false intimacy, the developing egocentrism of it, and the stick is terror and bodily fear, the fear of social interaction and alienation endemic to rampant materialism, and the fear of our mortality, which is ramped up to fever pitch by the practice of consumption.[22]

Examining my Tinder data history (which I requested from Tinder itself), I can see when and how many times I have opened the app (Fig. 4). A lot has changed since I first logged in to the application in terms of the hardware I own, the application’s software, and the interface I use to access the experience Tinder offers. My first Tinder profile was created on 6 April 2014, over five years ago. Since then, I have logged into my profile almost daily, depending on, among other factors, my relationship status and mood. Some days, I have logged in over a hundred times. Those days are followed by those with much less activity. What then pushes me to open and close the application one or even two hundred times? Some days, I swipe and sort through the infinite pool of potential matches that I have defined with my prerequisites, which is constantly filtered by my location in the world. Other days, I keep logging in and out of the application to respond to messages from a match. Deeper ambient intimacy and a developing connection with a new human, a potential lover, lead me to repeatedly log into the application.

Fig. 4. Screenshot of user login data requested from Tinder. Created by the author Nov. 2019.

I specifically reviewed my logins in April and May 2015 (Fig. 4). At the time, I had sprained my ankle, so I was desperate for a distraction and had a lot of time available to message potential matches. On 5 May 2015, I matched with an interesting man, with whom I chatted constantly for about a week. After we went on our first date, I would log in only sporadically. Eventually, I stopped logging in at all for the next three months that our relationship lasted. A day after our breakup, I logged in 150 times. It is fascinating to see how my login data so accurately describe my relationship status and emotional processes. My Tinder logins tend to increase when I am excited and frenetically messaging with a new match or when I am sad, lonely, and seeking a distraction and a form of ambient intimacy to alleviate my solitude. The continuous feed of information I have provided to the application provides a profile of my changing emotional states.

An application like Tinder follows me and gathers my data, remaining constantly accessible wherever I go. No matter how many devices or locations I change, Tinder is an omnipresent and constantly available dating aid. The logins might decrease or stop for months at the time, but I return to the application again and again. The stack of cards might change according to the geolocational data, but the processes of the Discovery and Messaging modes, as well as the act of sorting through an infinite stack of cards, remain the same. My dating patterns and personal preferences reside in Tinder’s data cloud, laid out and codified in ones and zeroes—six years of romance, relationships, failed dates, one-night stands, meaningful and meaningless sex, and thousands of messages exchanged with strangers in four cities. What is left for me to download are the links of the photos I uploaded and no longer use, some messages with matches who have remained on the app, and traces of my login patterns, but for me, this experience has been so much more than the data traces left behind. Tinder has been about absent loves, ambient intimacies, and movable objects of desire. Tinder has been an omnipresent vibration in my back pocket, a bit of flirtation, and at least the hope that, maybe, once a string attaches, the algorithm will bring me the right object, and my romantic outburst will have a more permanent recipient.

Pleasure and Fun in Swipe Life

“So it is a lover who speaks and says...”[23]

Now I travel and search the networks for new digital lovers.

Strings attached and detached.

Meaningless conversations help me push through the realm of time.

Thousands of unknown singles in pools of information.

Brian Massumi, influenced by Spinoza, defines affect as the capacity of the body for affecting or being affected.[24] He sees the ability to affect and be affected as two inseparable facets of the same event that happens between states and allows a transition to take place. He writes that “when you affect something, you are also opening yourself up to being affected in turn and in a slightly different way than you might have been the moment before.”[25] The pool of singles to whom I have access is constantly affected by the positioning of my smartphone and body in the world. My fingers reach out to touch the screen, but at the same time, I also touch others who are playing the same game as I am. I reach out and try to form a connection, constantly accumulating and reordering information, making dating choices and patterns visible to an invisible computational eye, and storing data in some spreadsheet I can’t control. All my data—all the exchanged messages, locations, and photographs—are stored and commemorated. What I do on the dating app leaves a trace behind and marks my routines: how I behave in the online dating world.

I do know all of this, and I am tired of moving my desire here and there, investing in ambient intimacies that might well vanish the next second. Something, though, keeps me addicted to this application, to this process of sorting men into stacks, choosing and determining whether they will enter my messaging board or not. In 1995, before smartphones and geolocation apps were ubiquitous, in his interview with Jérôme Sans, Paul Virilio described a shift between two realities: the concrete factual and the digital. Games, in the form of digital apps, penetrate reality, in a sense, almost forming a new reality of constant distraction. According to Virilio, “play is not something that brings pleasure; on the contrary, it expresses a shift in reality, unaccustomed mobility with respect to reality.”[26] The example he uses to further analyse this statement is the difference between meeting, loving, and making love to a person in the concrete world and using technology to have cybersex with someone from a distance without touching or risking real contact. Tinder requires both digital attention and then physical presence, mainly since making love still requires two individuals to share the same physical space. What Tinder turns into play is not the sex itself but the ability to meet people instantly and engage in a conversation with them without having to place your body outside your home.

What must be discussed here is the difference between fun and pleasure. Mark Blythe and Marc Hassenzahl argue that while “enjoyment,” “pleasure,” “fun,” and “attraction” are used interchangeably, there are important differences among forms of enjoyment.[27] They are differentiated in terms of “flow,” the peak experience of total absorption when engaging with dance or sport, and the micro-flows of unnecessary but engaging and satisfying activities that appear as distractions, such as chatting and doodling. Fun is characterised by the absence of seriousness and the ability to stop relating to the self—short, meaningless, repetitive intervals that serve as distractions. On the other hand, pleasure involves activities that require a specific devotion and allow someone to make sense of themselves and nourish their identities through them. Tinder allows a user to engage equally with both; the user has fun while swiping through matches in Discovery mode but must devote time to engage in conversation in Messaging mode to attain a date. Swiping time on Tinder is time within real time, usually empty time spent waiting for the bus or in fragments of boredom throughout the day.

In Politics of Affect, Massumi writes about the “micro shocks” that populate every moment of contemporary life. He describes a micro shock as “a shift of attention, an interruption, a momentary cut in the mode of onward deployment of life.”[28] Tinder is based on creating this type of shift in attention throughout the day, moving one’s focus in and out of the app, allowing what takes place in the Discovery and Messaging modes to influence one’s experience in the world and vice versa. The process of swiping seems to create two different worlds: the world in which you are present and the virtual world through which you swipe.

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Andrew Lison explore how software came to be considered as something fun, not focusing on the games or the users themselves but rather on the people who write the software: the programmers. The common ground that both gaming and programming share is “the double valence of fun: fun as enjoyment and fun as an obsession.”[29] They illustrate this idea with one of the first programmes that people learn to write when they begin programming, and they show how the production of an immediate result makes the programmer feel both power and enjoyment.[30] Tinder has transformed the act of swiping from a coded notion already charged with different uses into the most elemental binary meaning of “yes or no” for dating.

This binary decision, that of yes or no, transforms the Tinder user into the masterful subject, as discussed in the first section. This mastery over the stack of cards ties the format of the application back to desire and pleasure. We can better understand this through a psychoanalytical lens—more specifically the fort-da game explored in Sigmund Freud’s essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” and the mirror stage explored by Jacques Lacan, both stories that try to capture the emergence of subjectivity. Freud describes a game between his grandson and the child’s mother. The child, placed inside a crib, throws a toy outside the crib, and the mother brings it back. The child is entertained by the emergence and disappearance of the mother, with the feeling that it controls this emergence and disappearance, extracting pleasure from being the master of the situation.[31] Lacan’s mirror stage describes the moment when a child first recognises itself in a mirror and differentiates itself from the outside environment.[32] The child, in fact, misrecognises itself as capable and self-sufficient when, in reality, the child is neither of these things.

So, similar to these examples, when I use Tinder, I feel pleasure in ordering around the potential matches, feeling like a masterful subject, but actually, like the child in front of the mirror, I misrecognise myself as a subject because the game in which I am entangled is orchestrated by designers; my ability to interfere is actually both very limited and pleasurable by design. In the interface of Tinder, no one can stay out of the dance once they have entered. I swipe and judge, but I am also being swiped on and judged. I form connections with potential matches and exchange words and pleasurable or unpleasurable effects, but as I affect and I am affected, I am changed because of the constant flow of intensities and vibrations.

The swipes and taps conceal the deeper motive of finding a displaced object of desire, an “objét petit á” that might transform into a partner and bring my “swipe life” to an end. As one object of desire displaces the next, as one partner disappears and another emerges, the massive pool of potential matches is transformed into a constantly changing object of desire. I return to Tinder again and again for the comfortable blanket of ambient intimacy that creates pleasurable vibrations on my device. The high of meeting someone new can be repeated over and over, always accessible wherever I go. Only when the vibrations stop or a match disappears just for a minute do I become bothered, but then I return to the application because the fun and pleasure are too hard to resist and because I am too alone to handle it all.

Despite all the fun and pleasurable power vibrations that tone one’s subjectivity, what Tinder ultimately taps into is the desire to find, through the swipe, an object of desire, a partner, and a fulfilling relationship, even if that experience is short-lived. Swipe after swipe, the act of sorting through matches starts to become tedious, a constant interplay between Discovery mode and Messaging mode, the real and the virtual, fun and pleasure. The inability to find our object of desire becomes exhausting, but the loop of the seemingly never-ending pool of potential matches and the repetitively distractive act of swiping somehow drags us back into the application again and again.

[1] Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments Translated by Richard Howard (New York, Hill and Wang, 1978), 9.

[2] Barthes, 3.

[3] Laurel Fournier, Authotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), 13.

[4] “What Is Tinder?” Tinder, accessed 17 November 2019, https://www.help.tinder.com/hc/en-us/articles/115004647686-What-is-Tinder-.

[5] Barthes, 9.

[6] Merriam -Webster, s.v. “tinder (n.),” accessed 25 November 2019, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tinder.

[7] “Tinder Information, Statistics, Facts, and History,” Dating Sites Reviews, accessed 25 November 2019, https://www.datingsitesreviews.com/staticpages/indes.php?page=Tinder-Statistics-Facts-History.

[8] Benjamin H. Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereitnty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015), 237.

[9] Bratton, 221.

[10] Florian Cramer and Mathew Fuller, “Interface,” in Software Studies: A Lexicon, ed. Matthew Fuller (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 151–52.

[11] Sean Rad, “Inside Tinder: Meet the Guys Who Turned Dating into an Addiction,” interview by Laura Stampler, Time Magazine, February 2014, https://time.com/4837/tinder-meet-the-guys-who-turned-dating-into-an-addiction/.

[12] Bratton, 227.

[13] Rad, interview.

[14] Søren Pold, “Button,” in Software Studies: A Lexicon, ed. Matthew Fuller (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 34.

[15] Erica Biddle, “Info Nymphos,” MediaTropes 4, no. 1 (November 2013): 77.

[16] Biddle, “Info Nymphos,” 77.

[17] Barthes, 9.

[18] Reichelt, Lisa. “Ambient Intimacy.” Disambiguity, 1 Mar. 2017, http://www.disambiguity.com/ambient-intimacy/.

[19] Barthes, 13.

[20] Barthes, 15.

[21] Kaja Silverman, The Subject of Semiotics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 79.

[22] Biddle, 78.

[23] Barthes 9.

[24] Brian Massumi, The Politics of Affect (Durham: Polity, 2015), 3–4.

[25] Massumi, 4.

[26] Paul Virilio, “The Game of Love and Chance,” interview by Jérôme Sans, Grand Street 52, (April 1995): 12.

[27] Mark A. Blythe and Marc Hassenzahl, “The Semantics of Fun: Differentiating Enjoyable Experiences,” in Funology: From Usability to Enjoyment, ed.,Overbeeke,Monk and Wright, (Dodrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004), 91–100.

[28] Massumi, 53.

[29] WendyHui Kyong Chun and Andrew Lison, “Fun Is a Battlefield: Software Between Enjoyment and Obsession,” in Fun and Software: Exploring Pleasure, Paradox, and Pain in Computing, ed. Olga Goriunova (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 182.

[30] Chun and Lison, 177–81.

[31] Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle and Other Writings, trans. John Reddick (London: Penguin, 2003), 141–43,Electronic reproduction. [S.l.] : HathiTrust Digital Library, 2011.

[32] Jacques Lacan, Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans Bruce Fink (New York W. W. Norton & Co., 2006), 76.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Warren Sack for creating the ground to develop this paper, Anna Friz for insisting on always keeping my voice, Irene Gustafson for introducing me to the essayistic, Chris Vitale and Ethan Spigland for inspiring me to develop the first film version of this paper and Markella Demertzi for believing in my Tinder poetry. I would also like to thank the editorial board of Passage for their assistance in the editing process and the kind support of the Florence French Financial Aid Fund For Art Fellowship, by the University of California Santa Cruz.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1978.

Bey, Marquis. “On Lived Experience.” AAIHS, 2 Dec. 2019. https://www.aaihs.org/on-lived-experience/.

Biddle, Erika. “Info Nymphos.” MediaTropes 4, no. 1 (Nov. 2013): 65–82, https://doaj.org/article/a3b8509ee053456dab0b38c6ef699bdf.

Blythe, Mark A., and Marc Hassenzahl. “The Semantics of Fun: Differentiating Enjoyable Experiences.” In Funology: From Usability to Enjoyment, edited by Mark A. Blythe, Kees Overbeeke, Andrew Monk, and Peter Wright, 91–100. Dodrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004.

Bogard, William. “The Coils of a Serpent: Haptic Space and Control Societies.” Ctheory (Sept. 2007): 1. http://search.proquest.com/docview/275096627/.

Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong, and Andrew Lison. “Fun Is a Battlefield: Software Between Enjoyment and Obsession.” In Fun and Software: Exploring Pleasure, Paradox, and Pain in Computing, edited by Olga Goriunova, 177–81. New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Cramer, Florian, and Matthew Fuller. “Interface.” In Software Studies: A Lexicon, edited by Matthew Fuller, 149–52. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Dating Sites Reviews. Tinder Information, Statistics, Facts, and History. 2019. https://www.datingsitesreviews.com/staticpages/index.php?page=Tinder-Statistics-Facts-History.

Fournier, Lauren. Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021.

Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle and Other Writings. Translated by John Reddick. London: Penguin, 2003. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Lacan, Jacques. Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006.

Truffaut, François, dir. L’Histoire d’Adèle H. (The Story of Adèle H.). 1975; Beverly Hills, CA: MGM Home Entertainment, 2001. DVD.

Massumi, Brian. The Politics of Affect. Cambridge: Polity, 2015.

Pold, Søren. “Button.” In Software Studies: A Lexicon, edited by Matthew Fuller, 31–6. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Rad, Sean. “Inside Tinder: Meet the Guys Who Turned Dating into an Addiction.” Interview by Laura Stampler. Time Magazine, Feb. 2014. https://time.com/4837/tinder-meet-the-guys-who-turned-dating-into-an-addiction/.

Reichelt, Lisa. “Ambient Intimacy.” Disambiguity, 1 Mar. 2017, http://www.disambiguity.com/ambient-intimacy/.

Silverman, Kaja. The Subject of Semiotics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Thompson, Clive. “Brave New World of Digital Intimacy.” The New York Times, 7 Sept. 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/07/magazine/07awareness-t.html.

Tinder. “Introducing Feed.” Go Tinder, 2019. https://blog.gotinder.com/introducing-feed/.

Tinder. “What Is Tinder?” 2019. https://www.help.tinder.com/hc/en-us/articles/115004647686-What-is-Tinder-.

Virilio, Paul. “The Game of Love and Chance.” Interview by Jérôme Sans. Grand Street 52 (April 1995): 12–7.